I made a presentation about the

loss of the night app at the

13th European Symposium for the Protection of the Night Sky, and I wanted to share two important slides here. The first shows what fraction of our app users live under bright, or very bright skies:

The "Cinzano pop" tables show what population of the given countries were estimated in 2001 to live under skies 9 times or 27 times brighter than natural. At the bottom, we see that contributors to

GLOBE at Night and our app users are drawn from a population that is biased towards less polluted areas. This is a problem, because the app is designed for

urban astronomy! It only has the ~1000 brightest stars in its database, all of which have a magnitude less than 5. This means that more than 80% of all of our app users are making observations in areas that are too dark for the app to function properly!

There are three reasons why we don't have fainter stars in the app. First, we were on a tight money/time budget, so we just used the stars that were already in Google's Sky Map app. Second, if you are in an area with little skyglow, there are just so many stars in the sky that it's hard to tell which one the app is asking you to look for! Third, at some point the screen of the mobile phone will be bright enough that it will ruin your night vision and make it impossible to see the stars. Based on our testing, this isn't a problem in cities, but it would be in the countryside.

Does this mean that 80% of the data we have collected so far is useless? Far from it! Take a look at the next slide:

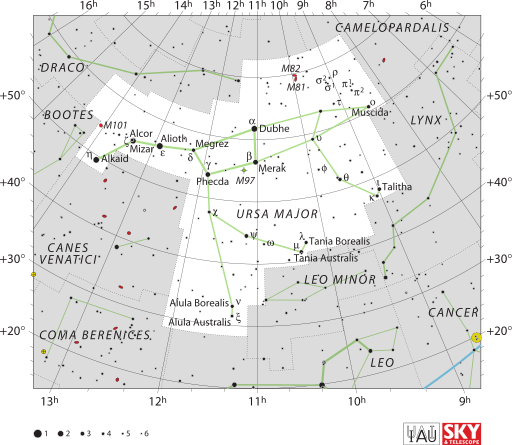

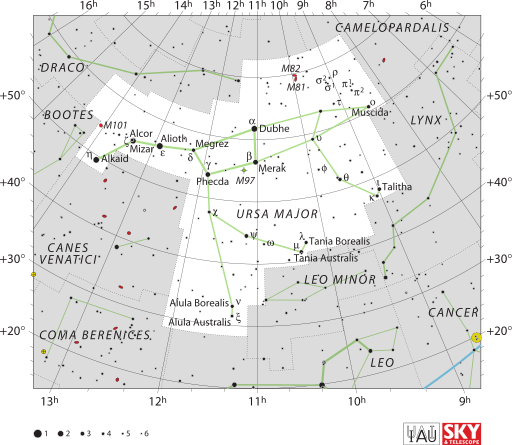

Here we compare two stars that are no so far away from each other in the Northern Hemisphere, Megrez in the Big Dipper and Edasich in Draco. You can see where the stars are relative to their constellations in the next two images:

|

| Megrez is the central star of the Big Dipper. |

|

| Edasich is a part of a much larger constellation. |

The two stars have a very similar brightness, but Megrez is part of the Big Dipper, probably the most familiar constellation in the Northern Hemisphere. Edasich, on the other hand, is part of Draco, a much more difficult constellation to observe. Because of this, our app users are able to make a decision about Megrez more quickly (20 seconds on average), and their decision is more accurate (nearly all of our app users should have been able to see both stars).

By using the app in an area without light pollution, you are helping us to understand which stars are easier to make quick, accurate decisions about, and which are harder. Once we have enough data about the 1000 stars in the database, we'll be able to preferentially assign easier stars to users. This will reduce the number of incorrect classifications, and will probably also make the app more fun. So use the app wherever you happen to be, but

please tell your friends living in cities to try out the app!